The Road to 1974: The Cyprus issue breaks through the Anglo-Hellenic bond

After making a token effort at consensus with Britain, Cyprus’ Makarios sought self-determination at the UN in 1954, dividing his own support base and alienating NATO

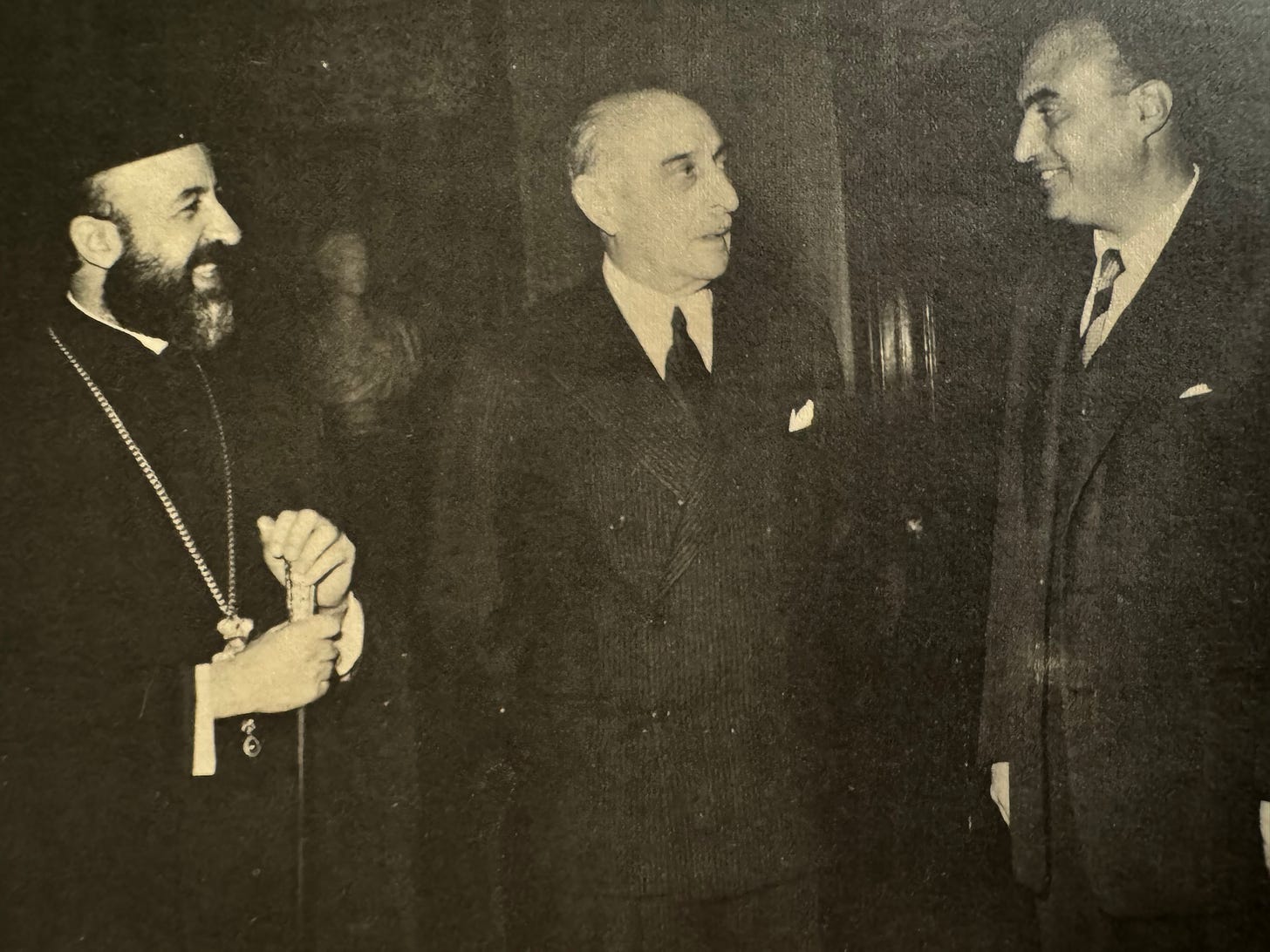

On October 20, 1950, The Metropolitans of Cyprus elected Archbishop Makarios III as Archbishop and de facto national leader of the Greek-Cypriots, with the title Ethnarch (Εθνάρχης), which had accrued to the leaders of the island’s Christian flock during the centuries of Ottoman dominion. In January of that year, 95.7 percent of Greek-Cypriots had voted for Union (Enosis) of their island with Greece. The referendum and Makarios’ election marked a turning point in the island’s quest.

Makarios’ reputation was that of a conservative nationalist, a believer in the Great Idea (Μεγάλη Ιδέα) politics of Eleftherios Venizelos, whose quest for a Greek empire in Asia Minor had ended in catastrophe at the hands of his political enemies, the royalists, in 1922.[1] Makarios believed he could redeem the idea of a Greater Greece through its unification with Cyprus. To do so, he would have to wrest it from the British, who had come into its de facto possession in 1878 and officially colonised it in 1925.

Makarios shortly after his enthronement visited Athens to seek Greek support for the Cypriot cause. He had reason for hope. Sophoklis Venizelos, the son of Eleftherios, was prime minister, Greece had been reunited with the Dodecanese with its allies’ blessings two years earlier, and the previous year had secured peace and territorial integrity by defeating its insurgent communists in a civil war that had lasted as long as the Second World War. But the politicians in Athens were not ready for adventure. A council of party leaders communicated to Makarios that while “free Greece cannot be indifferent to any segment of unredeemed Hellenism… less now than ever is it prepared to depart from its traditional friendship [with Great Britain].” Athens sought a consensual foreign policy, in which the Greeks of Cyprus were joined to Greece, Britain maintained its military bases, which were of strategic importance, and the rights of the Turkish-Cypriot minority (18 percent of the population) were assured. Athens judged that the pursuit of this consensual goal would have to wait, given the “other urgent matters attending Great Britian”.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hellenica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.