The Road to 1974: Makarios Poisons Greek Politics

In March 1957, the Greek government secured Archbishop Makarios’ release from exile in the Seychelles, and was saddled with a toxic political presence

On 29 March 1957, the British government freed Makarios from exile in the Seychelles, with permission to go anywhere except his native Cyprus. Angelos Vlachos, the Greek consul to Nicosia, described the scene at 6pm, when the news was broadcast:

“From the centre of Nicosia a cry went up which grew louder and closer, and a frenzied crowd surrounded the consulate with shouts and songs. The sun was setting but I told the porter not to lower the flag from its high mast and to turn on the lights in the garden. Lights, inarticulate cries of joy, scanning slogans, unending songs, “Long live”, sprang from the crowd. Students, young people, professionals, teachers, workers, embarked on a spontaneous, sloppy circular parade that lasted until three in the morning. I stood at the top of the staircase leading to the roof and waved with both arms until my shoulders were sore. The porter, Theofanis, brought me water every so often because my throat would dry out from shouting along with the crowd and singing the national anthem.”[1]

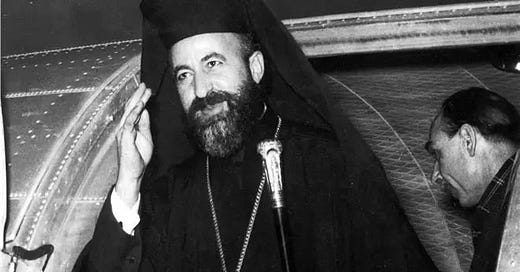

Shipowner Aristotle Onassis laid on a tanker, Olympic Thunder, to transport Makarios as far as Madagascar, where he caught an Air France flight to Athens. There, he received a national hero’s welcome on April 17, with crowds travelling out to the Hellenikon airport to wait for him early in the morning, and lining the streets in Phaleron through which his motorcade would pass. King Paul sent his limousine to pick up the Archbishop. From a balcony in the Grande Bretagne hotel, Makarios delivered a speech to a packed crowd in Syntagma Square.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hellenica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.